Punk style returned with a vengeance -- at least among a small but influential group of designers who presented their spring 2011 collections here last week. But this time, the raw, aggressive, do-it-yourself aesthetic, born in London and New York in the 1970s to serve as a howl of anger and disgruntlement, took up residence in some of this city's most elite locations. Studs and safety pins, shredded jeans and torn T-shirts were unveiled in the gilded salons of the Hotel du Crillon, the Westin, a private atelier.

As a result, this new version of punk seemed less of a belligerent, confrontational assault on the powers-that-be and more of a polished, polite whisper of disaffection. Could it be that fashion has lost its ability to piss anyone off? Is it no longer capable of anything more than just some ill-mannered faux pas or cultural gaffe that has observers tsk-tsking? Can fashion no longer voice a truly hard-to-stomach statement that riles the culture and eloquently expresses roiling societal anger and resentment?

It has been a long time since there was any fashion movement that truly upset the sensibilities. Hip-hop fashion was the last aesthetic that caused unrest, but big brands like McDonald's realized lickety-split that tapping into hip-hop culture would be a fine way of attracting those young customers who'd long ago transitioned out of Happy Meals but were just beginning to buy their own junk food.

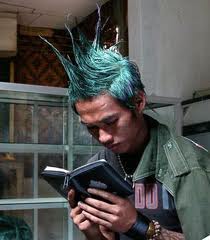

The result is that when fashion wants to rage against the ruling class, it doesn't have many alternatives. A pierced eyebrow isn't going to raise many hackles. Tattoos are commonplace. Mohawks are salon-approved.

Much of what was on the runway would best be described as "punk lite." At Balenciaga, designer Nicolas Ghesquière used punk style as a launching point for a collection that was more interested in fashion experimentation than political upheaval.

Designer Riccardo Tisci created a collection for Givenchy that had its roots in a punk sensibility with its zipper-embellished motorcycle jackets and heavy reliance on black and sharp silhouettes. But mostly, punk was a subtext, a mood that ran through a collection that spent just as much time emphasizing leopard prints and sheer chiffon skirts.

For Tisci, punk was just another way for him to express his dark, vaguely gothic sensibility, which defines the Givenchy collection but also severely limits its creative breadth.

It was Christophe Decarnin at Balmain and Jean Paul Gaultier who seemed to embrace the philosophy of punk as well as its styling tactics. Decarnin was the most literal in his interpretation, with a collection that featured enough safety pins to reach from Paris to your local Office Depot. The irony, of course, is that punk style was based on shunning blowhards and moneybags. So watching the Balmain parade of fashion unfold in an establishment hotel salon and knowing that the studded jackets would easily cost $20,000 and those nearly disintegrating T-shirts would be upwards of $1,000, made one cringe.

Decarnin doesn't have a responsibility to maintain the original meaning of a sensibility that has long been in the public domain. And it would be easy to dismiss the Balmain customer as someone with more money than good sense. But in some ways, it may be that Decarnin has artfully upended the meaning of punk style.

If conventional wisdom tells us that lavish displays of wealth are unseemly while so many people suffer economically, the Balmain collection was a middle finger to that decorum. Its subversive message was "look at me," when everyone else is running for cover.